|

Home

Up

Search

Multi-County DVDs

Missouri Counties

Southeast Missouri

Ozark Region

Arkansas Counties

Illinois Counties

Indiana Counties

Iowa Counties

Kansas Counties

Kentucky Counties

Louisiana Parishes

Massachusetts Vital Records

North Carolina Counties

Ohio Counties

Pennsylvania Counties

Tennessee Counties

Texas Counties

Historic Map Reprints

Plat Map Books

Census Records

State County Maps

New Titles

Coming Soon

Questions Answers

Customer Quotes

Wholesale

Conferences

Missouri Journey

Iris Median

Contact Us

Genealogy History News

Special Offers

County History Books

| |

When The Skies Turned To Black

The Locust Plaque of 1875

A study of the intersection of

history and genealogy

Ever wonder why your ancestors suddenly left an area and moved to a distant

region? Or, why did they return to the same area that they originally came from?

If you had family who lived in the States of Kansas, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas or the western

portions of Iowa, Missouri, or Minnesota in the mid 1870’s, chances are they

were witnesses of the devastating plagues of locusts that swept over the region.

Lush gardens and fields of a wide range of crops were reduced to a barren,

desert like appearance within a matter of hours. Crops that were needed to

sustain a family and their farm animals were destroyed leaving no means of

support during the coming winter.

As early as records are available, the central region of the United States has

had occasional times when locusts would increase in number and quickly devour

crops over a large region. None of the previous invasions were nearly as

devastating as what would become known as The Year of The Locust: 1875. Nothing

like it in the United States had been recorded before and nothing like it has been seen since.

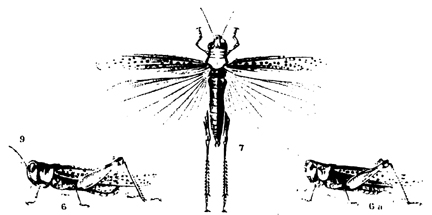

What could cause such devastation and panic? The answer is a relatively small

flying grasshopper, roughly 1.25 to 1.4 inches long, known as the Rocky Mountain

Locust. Individually, they were rather unimpressive and caused little problem.

When conditions were ideal, they could multiply into the billions, travel over

long distances, and consume virtually anything and everything that was remotely

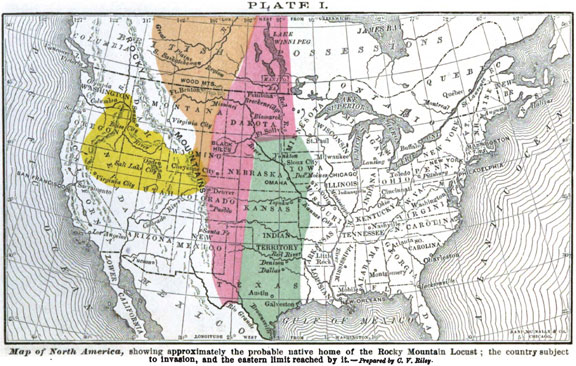

edible. Their native homelands were the dry Rocky Mountain upland region of

primarily Colorado, Wyoming and Montana. After hatching out in the spring of the

year, the locusts would travel eastward in search of food. In years where the

number of those hatched was unusually large, the food supply was stripped rather

quickly driving them ever eastward in search of new food supplies. Kansas and

Nebraska were usually among their first targets and were frequently the most

devastated but the swarms spread over a large area stretching north from the

interior of Canada and extending all the way to the south border of Texas. The

eastern regions of Nebraska and Kansas along with the western regions of

Minnesota, Iowa, and Missouri were the areas most devastated.

The Year of the Locust actually began with the first arrivals of the swarms in

the mid summer of 1874. They reached the northwestern corner of Missouri in late

July to early August. Within the coming weeks, the locusts continued their trek

in a southeast direction until they reached the limits of their travel. Most of

the heavy damage in 1874 was limited to Kansas and Nebraska. Damage was rather

light in Missouri 1874 but the appearance of such huge numbers of the insects

caused a great deal of panic of what was feared to be coming in the spring of

1875. The fears were realized by late April of 1875 when the spring hatch out

began. The numbers have since been estimated to be in the trillions, an

unimaginable number that has no match in all of recorded history. Consider this

quote from "Voices from the Past: What We Can Learn from the Rocky Mountain

Locust" by Jeffrey A. Lockwood:

“According to the first-hand account of A. L. Child transcribed by Riley et

al. (1880), a swarm of Rocky Mountain locusts passed over Plattsmouth, Nebraska,

in 1875. By timing the rate of movement as the insects streamed overhead for 5

days and by telegraphing to surrounding towns, he was able to estimate that the

swarm was 1,800 miles long and at least 110 miles wide. Based on his

information, this swarm covered a swath equal to the combined areas of

Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New

Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont.”

Nearly every county

history from the late 1800’s in the affected areas records an account of the

devastation within their own borders. The following are quotes from several of

these county histories:

“It was the year 1875 that will long be remembered by the people of at least

four states, as the grasshopper year. The scourge struck Western Missouri April,

1875, and commenced devastating some of the fairest portions of our noble

commonwealth. They gave Henry [County] an earnest and overwhelming visitation,

and demonstrated with an amazing rapidity that their appetite was voracious, and

that everything green belonged to them for their sustenance. They came in

swarms, they came by the millions, they came in legions, they came by the mile,

and they darkened the heavens in their flight, or blackened the earth's surface,

where in myriads they sought their daily meal. Henry County was visited from

about the first week of May, and remained until the 1st of June, 1875, and

during that time, every spear of wheat, oats, flax and corn were eaten close to

the ground. Potatoes and all vegetables received the same treatment, and on the

line of their march, ruin stared the farmer in the face, and starvation knocked

loudly at his door.”

The History of Henry and St. Clair County, Missouri. 1883, National

Historical Company, St. Joseph, Missouri

“The invasion of

Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado and Western Missouri, by the grasshoppers; or more

properly speaking, the Rocky Mountain Locusts, in 1874, occurred in the month of

August; and was fraught with great disaster to the agricultural interests of

those States and to the trade of Kansas City. The locusts came in immense clouds

and literally covered the territory mentioned. Their first appearance was

generally at a great altitude, flying from the northwest to the southeast, and

their appearance was that of a snow storm. Sometimes they were so numerous as to

darken the sunlight. They settled gradually to the ground, when their voracity

soon made itself apparent; whole fields of green corn being destroyed in a

single day. Nothing escaped them; there appeared to be nothing they would not

eat; at least there was nothing that they did not eat; and in their progress

they left the country nearly as bare of vegetation as if it had been scorched by

fire. By the time they reached the Missouri River section, vegetation, at least

the crops, was too far advanced for them to do material harm, but on the

frontiers, where they appeared earlier, and where the new settlers' dependence

was a crop of sod corn, necessarily late and immature, their destruction was

great and caused much suffering during the following winter. They matured

sufficiently to begin to deposit their eggs when about fifty miles west of

Kansas City, and continued until they had advanced to about fifty miles east of

it. Hence, in the spring of the year 1875, a new crop was hatched to infest the

country, and they proved no less voracious than their progenitors of the year

before. A district about a hundred miles wide extending southward from Kansas

City a hundred miles and northward to the British possessions, was kept as bare

of vegetation as midwinter until June of 1875, when the young brood suddenly

took wing and disappeared as mysteriously as their progenitors had appeared,

going in a northwesterly direction. The effect of all this was to cost the

larger part of the country united by them the bulk of a year's crop, part of it

in the fall of 1874, and part in the spring of 1875. Such disaster could not but

affect detrimentally the business of Kansas City. Early in the winter of 1874-5

it was ascertained that there was great suffering among the people of western

Kansas from this cause, and organized efforts for relief began to be made. The

east was appealed to and responded liberally.”

The History of Jackson County, Missouri. 1881, Union Historical Company,

Birdsall, Williams & Co., Kansas City

* * *

"1875- 'Serious and distressing,' says Mr. Riley, 'as were the ravages of this

insect in 1874, when the winged swarms overswept several of the western states,

and poured into our western counties in the fall, the injury and suffering that

ensued were as naught in Missouri, compared to what resulted from the unfledged

myriads that hatched out in the spring of 1875.' 'The greatest damage extended

over a strip twenty-five miles each side of the Missouri river, from Omaha to

Kansas City, and then extending south to the southwestern limit of Missouri-and

Bates, Buchanan, Barton, Clay, Cass, Clinton, Henry, Jackson, Johnson,

Lafayette, Platte, St. Clair, and Vernon, suffered most. Early in May, the

reports from the locust districts of the state were very conflicting; the

insects were confined to within short radii of their hatching-grounds. The

season was propitious, and where the insects did not occur, everything promised

well. As the month drew more and more to a close, the insects extended the area

of destruction, and the alarm became general. By the end of the month, the

non-timbered portions of the middle western counties, were as bare as in winter.

Here and there patches of Amarantus blitem, and a few jagged stalks of milk-weed

(Asclepas) served to relieve the monotony. An occasional out-field, or low piece

of prairie, would also remain green; but with these exceptions one might travel

for days by buggy and find everything eaten off, even to underbrush in the

woods. The suffering was great and the people well nigh disheartened. Cattle and

stock of all kinds, except hogs and poultry, were driven away to the more

favored counties, and relief committees were organized. Many families left the

state under the influence of the temporary panic and the unnecessary forebodings

and exaggerated statements of the pessimists. Chronic loafers and idlers even

made some trouble and threatened to seize the goods and property of the

well-to-do. Relief work was, however, carried on energetically, and with few

exceptions, no violence occurred.”

“In his eighth annual report Mr. Riley (then state entomologist of Missouri)

thus estimates the loss in the various counties of Missouri in 1875: Atchison,

$700,000; Andrew, $500,000; Bates, $200,000; Barton, $5,000; Benton, $5,000;

Buchanan, $2,000,000; Caldwell, $10,000; Cass, $2,000,000; Clay, $800,000;

Clinton, $600,000; De Kalb, $200,000; Gentry, $400,000; Harrison, $10,000;

Henry, $800,000; Holt, $300,000; Jackson, $2,500,000; Jasper, $5,000; Johnson,

$1,000,000; Lafayette, $2,000,000; Newton, $5,000; Pettis, $50,000; Platte,

$800,000; Ray, $75,000; Saint Clair, $850,000; Vernon, $75,000; Worth, $10,000.

Amounting in the aggregate to something over $15,000,000.”

“The vastness of the depredations of the insect are better appreciated when it

is stated that the locust area comprised nearly two million square miles, and

that Missouri suffered on an average with the other states within that section.

It is estimated that the aggregate loss in the destruction of crops alone would

reach $100,000,000, and that the indirect stoppage in business, and the crushing

of new enterprises made fully as much more, so that direct and indirect loss was

not less than $200,000,000. Mr. F. V. Hayden, U. S. geologist, in this

connection says: "In addition to all this, we must include as a part of the

effect of locust injuries, the checking of immigration, and the depreciation in

the value of lands. So depressing, in fact, was this result in some regions as

to paralyze trade, put a stop to all new enterprises, and dishearten the

communities where the suffering was greatest."

The History of Johnson County, Missouri. 1881, Kansas City Historical

Company, Kansas City, MO

“These were the years of the great devastation in Nebraska, Kansas, and western

Missouri by the Rocky Mountain locust (Caloptemus Spretus). The locusts came in

thick flying clouds, mostly from a west or northwesterly direction, in the fall

of 1874; they destroyed what they could find then that was green and juicy

enough for them, and finally laid their eggs. Lafayette county did not suffer

greatly this year, as compared with other counties further west and north. But

when the little imps hatched out in the spring and commenced marching eastward,

eating a clean swath as they went, then this county knew what it was to be "grasshoppered."

A correspondent of the Chicago Times wrote from Lexington, May 18, 1875: "The

grasshoppers are on the move east, eating everything green in their road. One

farmer south of this city had fifteen acres of corn eaten by them yesterday in

three hours. They mowed it down close to the ground just as if a mowing machine

had cut it. All the tobacco plants in the upper part of the county have been

eaten by them.’”

The History of Lafayette County, Missouri. 1881, Missouri Historical Company,

St. Louis, MO.

* * *

"Their flight, may be likened to an immense snow-storm, extending from the

ground to a height at which our visual organs perceive them only as minute,

darting scintillations, leaving the imagination to picture them indefinite

distances beyond. 'When on the highest peaks of the Snowy Range, fourteen or

fifteen thousand feet above the sea, I have seen them filling the air as much

higher as they could be distinguished with a good field-glass. It is a vast

cloud of animated specks, glittering against the sun. 0n the horizon they often

appear as a dust tornado, riding upon the wind like an ominous hail-storm,

eddying and whirling about like the wild, dead leaves in an autumn storm, and

finally sweeping up to and past you, with a power that is irresistible. They

move mainly with the wind, and when there is no wind they whirl about in the air

like swarming bees. If a passing swarm suddenly meets with a change in the

atmosphere, 'such as the approach of a thunderstorm or gale of wind, they came

down precipitately, seeming to fold their wings, and fall by the force of

gravity, thousands being killed by the fall if it is upon stone or other hard

surface.'"

"An idea of the vast numbers that will sometimes descend to the ground may be

formed by the following occurrence, related to us by an intelligent and reliable

eye-witness, Mr. H. McAllister, of Colorado Springs, Colo.: In 1875, early in

August, a swarm suddenly come down at that place. The insects came with the

wind, and alighted in a rain. The ground was literally covered two and three

inches deep, and glittered "as a new dollar" with the active multitude. In

rising, the next day, by a common impulse, their wings would get entangled, and

they would drop to the ground again in a matted mass. "In alighting, they circle

in myriads about you, beating against everything animate or inanimate, driving

into open doors and windows, heaping about your feet and around your buildings,

their jaws constantly at work biting and testing all things in seeking what they

can devour. In the midst of the incessant buzz and noise which such a fight

produces, in face of the unavoidable destruction everywhere going on, one is

bewildered and awed at the collective power of the ravaging host, which calls to

mind so forcibly the plagues of Egypt."

"The noise their myriad jaws make when engaged in their work of destruction can

be realized by any one who has 'fought' a prairie fire or heard the flames

passing along before a brisk wind-the low crackling and rasping; the general

effect of the two sounds is very much the same."

"Persons in the East have often smiled incredulously at our statements that the

locusts often impeded the trains on the western railroads. Yet such was by no

means an infrequent occurrence in 1874 and 1875-the insects pawing over the

track or basking thereon so numerously that the oil from their crushed bodies

reduced the traction so as to actually stop the train, especially on an

up-grade."

Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture For The Year 1877. Washington, DC

1878.

* * *

"The severely

stricken region, covering an area variously estimated at from 200 to 275 miles

from east to west, and from 250 to 350 miles from north to south, and embracing

portions of Nebraska, Kansas and Missouri, presented a variety of experience,

some portions being comparatively exempt from injury, while others wore an

aspect of devastation that changed the verdure of spring into the barrenness of

winter."

"The tract in which the injury done by the destructive enemy was worst, was

confined to the two western tiers of counties in Missouri, and the four tiers of

counties in Kansas, bounded by the Missouri river on the east. The greatest

damage extended over a strip 25 miles each side of the Missouri river, from

Omaha to Kansas City, and then extending south to the southwestern limit of

Missouri. About three-quarters of a million of people were to a greater or less

extent made sufferers. The experience of different localities was not equal or

uniform. Contiguous farms sometimes presented the contrast of abundance and

utter want, according to the caprices of the invaders, or according as they

hatched in localities favorable to the laying of the eggs. This fact gave rise

to contradictory reports, each particular locality generalizing from its own

experience. The fact is, however, that over the region described there was a

very general devastation, involving the destruction of three-fourth of all field

and garden crops. While the injury was greatest in the area defined above, the

insects hatched in more or less injurious numbers from Texas to British

America-the prevalence of the insects in Manitoba being such that in many parts

little or no cultivation was attempted."

The Locust Plague in the United States by Charles V. Riley. 1877, Rand,

McNally & Co., Chicago.

* * *

"In 1875, near Lane, Kansas, they crossed the Potawotomie Creek, which is about

four rods wide, by millions; while the Big and Little Blues, tributaries of the

Missouri, near Independence, the one about 100 feet wide at its mouth, and the

other not so wide, were crossed at numerous places by the moving armies, which

would march down to the water's edge and commence jumping in, one upon another,

till they would pontoon the stream, so as to effect a crossing. Two of these

mighty armies also met, one moving east and the other west, on the river-bluff,

in the same locality, and each turning their course north and down the bluff,

and coming to a perpendicular ledge of rock 25 or 30 feet high, passed over in a

sheet apparently 6 or 7 inches thick, and causing a roaring noise similar to a

cataract of water."

Riley's Eighth Report, p. 118. recorded in First Annual Report Of The United

States Entomological Commission For The Year 1877 Relating To The Rocky Mountain

Locust

Other historical accounts have recorded that after the crops were devoured, the

locusts turned to the trees, consuming the leaves and stripping the bark from

the trees. There are some accounts that fence posts, axe handles, cloth, leather

stirrups, bridles, and gloves were also chewed and consumed in their never

ending search for food.

By late June, the locusts had done their worst and vanished as quickly as they

had arrived. Most reports state that the swarms took flight in a northwest

direction, apparently returning in the direction from which they had originally

come. Despite the lateness of the date, the people went to work in hurriedly

replanting their gardens and crops with hopes and prayers that the crops would

have enough time to mature before winter arrived. Corn was planted as late as

July 4th, which is quite late since most corn in Missouri is planted in May to

very early June. A typical Missouri summer is hot and dry so early planting is

essential to give a reasonable chance of a successful crop. The year of 1875 was

not a typical year. The rains were plentiful and the season was longer than

usual. The result was record crops that far exceeded the yield of a typical

year. Some areas in Missouri actually were able to grow a surplus of crops which

were shipped to the hardest hit areas of Kansas and Nebraska. It was a joyous

and surprise ending to what was expected to be a time of extended desperation

with a bleak winter ahead.

While the surprisingly successful season brought much relief, there continued to

be a general fear that the next spring would see a return of the hordes of

locusts. The locusts did return to some degree in the following two years. A

great deal of study was made to attempt to control any future invasions.

Numerous inventions were patented that were supposed to be of value in combating

the pests. Most of the states made efforts to control the locusts by a wide

range of means. Bounties were paid for the collection of quantities of the

locusts, usually of $1 per bushel. Nicollet County, Minnesota paid $25,053 for

25,053 bushels of locusts while some counties paid out even higher amounts. It

will never be known if these attempts really made much difference

While they continued to be destructive, they were always much less so than in

1875. Never again were they as great of a threat as they had been during that

memorable year. Then, surprising, they simply disappeared, never to be seen

again. The last recorded sighting of the Rocky Mountain Locust was in 1902.

Why did they disappear? A number of theories have been proposed but none seem to

provide a completely satisfactory answer. One suggestion is that the widespread

settlement of the prairie and the resulting plowing that was done may have

disrupted the locusts reproductive success since they laid their eggs in the

soil. A number of rainy years may have played a role since their greatest

reproductive success was when they laid their eggs in dry soil.

While many by their own choice did stay through all of the difficulties, others

who stayed simply had no choice but to stay, they were too destitute to move on.

Others, particularly in Kansas and Nebraska thought it best to cut their losses

moved away, mostly east outside of the area affected by the repeated plagues.

The plagues, for a time at least, slowed and some areas actually reversed the

migration into the most affected prairie region. Do you have ancestors who

without explanation moved from the counties in this region in the mid to late

1870’s? There is an excellent chance that the now extinct Rocky Mountain Locust

played a significant role in their decision.

Find more related articles concerning

history and genealogy here: The

Lives of Our Ancestors including:

An Unforgettable

Wedding

An

Execution by Burning at the Stake

The New

Madrid Earthquake of 1811-12

Historical Map Reprints

Additional

Free Genealogy and Map Resources

|